Rock Interviews

NEVERTEL

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-06-07T18:18:36-07:00June 7th, 2025|

RETURN TO DUST

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-04-02T21:08:28-07:00April 2nd, 2025|

NATHAN JAMES

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-03-20T20:21:27-07:00March 20th, 2025|

DEMON HUNTER’s Ryan Clark

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-02-08T18:12:16-08:00February 10th, 2025|

TWIZTID

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-02-08T11:49:56-08:00February 6th, 2025|

SPLIT PERSONA’s Zander Joel

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-02-06T15:51:14-08:00November 21st, 2024|

VELVET CHAINS’ Nils Goldschmidt

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-02-06T15:52:01-08:00November 12th, 2024|

ZERO 9:36

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-02-06T15:55:12-08:00September 11th, 2024|

30 Years of Hopeless Records

By Ryan J. Downey|2024-09-27T15:33:03-07:00August 13th, 2024|

PISTOLS AT DAWN

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-02-06T15:56:41-08:00August 8th, 2024|

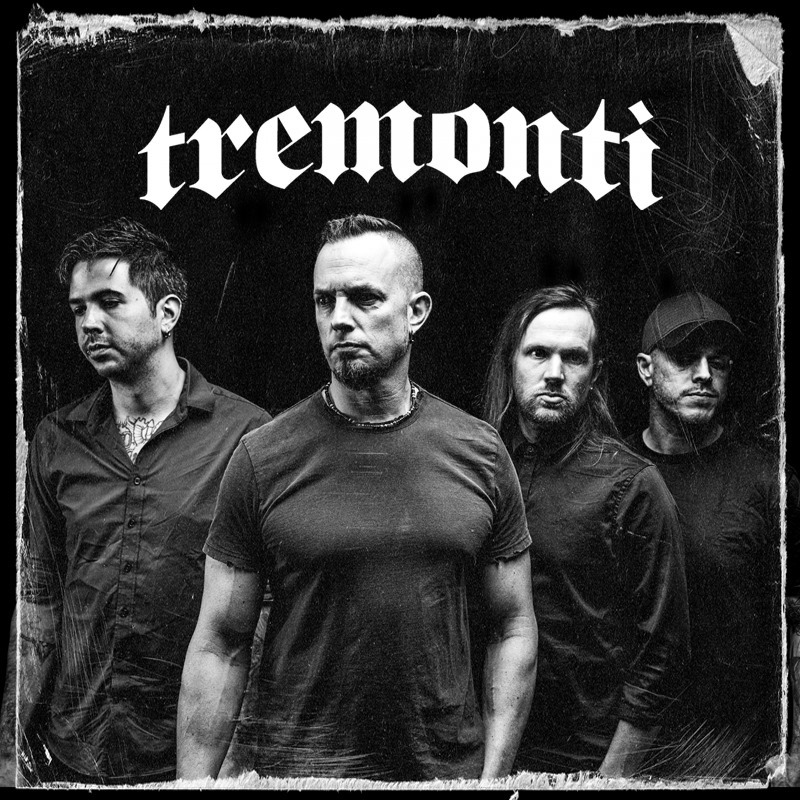

MARK TREMONTI

By Ryan J. Downey|2025-02-06T15:57:58-08:00August 6th, 2024|

In Conversation with BADFLOWER’S JOSH KATZ

By Ryan J. Downey|2024-09-27T15:33:07-07:00August 1st, 2024|

In Conversation with JAGER HENRY

By Ryan J. Downey|2024-09-27T15:33:07-07:00July 30th, 2024|

In Conversation with MYLES KENNEDY

By Ryan J. Downey|2024-09-27T15:33:44-07:00June 12th, 2024|

Manafest

By Ryan J. Downey|2024-09-27T15:34:14-07:00June 3rd, 2024|